Hilda Terry challenged an “all-boys” cartoonist club of the early 1900’s, and won.

The National Cartoonists Society had been a mens’ club since its formation in 1946. It had been founded by a group of New York cartoonists who had discovered they enjoyed the pleasure of each other’s company while doing chalktalks for soldiers convalescing in hospitals in the area during the World War II. One of the group, C.D. Russell (Pete the Tramp) had begun advocating that they form a cartoonists club— “but no girls,” he’d say, staring at Toni Mendez, erstwhile Rockette from Radio City Music Hall, who was the cartoonists’ connection to the American Theater Wing, the sponsor of the chalktalk series. Mens’ clubs were not at all unusual at the time. There were several (Friars, Lambs, etc.) in New York that served as models for NCS; all were vestiges of an earlier age, admittedly, but they were there.

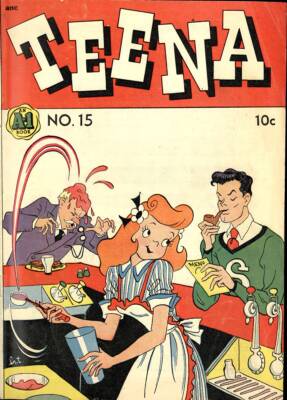

By the fall of 1949, NCS had begun to make itself visible, chiefly by mounting exhibitions of original cartoon art in the New York vicinity and by doing chalktalks for charitable purposes — among them, that fall, a national tour to sell U.S. savings bonds. In the midst of the bond tour, NCS President Milton Caniff (Steve Canyon) had received a letter from Hilda Terry, wife of the Society’s secretary Greg d’Alessio and creator of Teena, a comic strip about teenagers. Terry was writing as spokesperson for several women cartoonists, who had had about all they could take of the male exclusivity upon which the Cartoonists Society had been so defiantly founded. A social club for the boys had been all right, she pointed out, but the more visible the club became as a professional association, the more damaging it was for women cartoonists to be excluded from membership. Terry presented the argument concisely, and its logic was unassailable (in italics):

Gentlemen:

While we are, individually, in complete sympathy with your wish to convene unhampered by the presence of women, and while we would, individually, like to continue, as far as we are concerned, the indulgence of your masculine whim, we find that the cost of your stag privilege is stagnation for us, professionally. Therefore, we appeal to you, in all fairness, to consider that:

WHEREAS your organization displays itself publicly as the National Cartoonists Society, and

WHEREAS there is no information in the title to denote that it is exclusively a men’s organization, and

WHEREAS a professional organization that excludes women in this day and age is unheard of and unthought of, and

WHEREAS the public is therefore left to assume, where they are interested in any cartoonist of the female sex, that said cartoonist must be excluded from your exhibitions for other reasons damaging to the cartoonist’s professional prestige,

We most humbly request that you either alter your title to the National Men Cartoonists Society, or confine your activities to social and private functions, or discontinue, in effect, whatever rule or practice you have which bars otherwise qualified women cartoonists to membership for purely sexual reasons.

Sincerely, The Committee for Women Cartoonists

Hilda Terry, Temporary Chairwoman

Caniff read the letter to the October 26 meeting of the Society, and as soon as he had finished, Lou Hanlon rose and announced that he was in favor of admitting women to membership “for purely sexual reasons.”

Quips and japes aside, everyone in the room knew that Terry had raised an issue that would not, now, go away until it was resolved. And resolving it could split the membership into opposing factions. There were still members of the Society who wished passionately to maintain the marching and chowdering group as a wholly masculine redout. And the gender restriction wasn’t simply a question of custom: the Society’s constitution laid down the rules of eligibility for membership, specifying that “any cartoonist (male) who signs his name to his published work” could apply for membership. The matter would have to be referred to the entire membership, and that was certain to promote bad feeling in some corners.

The November Newsletter printed Terry’s letter and a coupon for members to return, expressing their opinions on the question of women in the ranks. The results were reported at the November 30 meeting: women were overwhelmingly approved for membership. A vote conducted at the same meeting validated the opinion poll. And Hilda Terry was promptly put up for membership, the first woman candidate. (“I’d rather look at her across the dinner table than Otto Soglow,” said Mel Casson in seconding Terry’s nomination.)

Later, when Mike Angelo in Philadelphia read the report of the meeting in the December Newsletter, he did his duty as a member and went out recruiting. He asked the well-known magazine gag cartoonist Barbara Shermund if she’d be interested in joining. She was, so Angelo sent her name in to the Membership Committee, the second woman candidate.

The Membership Committee, following its prescribed routine, reviewed the qualifications of all applicants for membership and then submitted the names of those who passed muster to the entire membership for a vote. At the regular meeting at the end of December, Alex Raymond, chairman of the Membership Committee, reported on the most recent of the Committee’s deliberations:

“We held a referendum in this Society about women members,” he said. “We voted and gave them the privilege of joining. I believe that we should admit people for professional ability alone. We must now vote upon the candidacy of women as they are received by my committee. We will treat them as the men. As a result, we have passed on Hilda Terry, Barbara Shermund as well as George Shellhase and Lee Elias.”

The members voted on all four candidates by mail ballot during the week before the next month’s meeting on January 25. In common with most New York clubs of the day, NCS employed the blackball to deny membership to an individual: three negative votes were enough to end a person’s quest for membership in the Society. Astonishingly, both Terry and Shermund received three negative votes. The issue of feminine membership, which everyone thought had been settled at the November meeting, was suddenly, rudely, re-opened. When the results of the balloting were announced at the January 25 meeting, the room exploded.

Consternation and confusion. Willard Mullin and Greg d’Alessio and several others walked out in disgust. Al Capp would have left, too, but the speaker of the evening, the distinguished censorship expert lawyer Morris Ernst, was his guest, and Capp didn’t feel he could abandon the attorney. Alfred Andriola also wanted to leave but felt obliged to stay in order to be able to report the evening’s developments in the next Newsletter.

Caniff was incensed, his Irish temper (not often on display) aroused. He delivered an angry Presidential lecture.

“The all male thing, that was wrong,” he told me when I asked him about it. “It just didn’t make sense. Cartooning has nothing to do with sex. It was just wrong, that’s all. Absolutely wrong ”

The meeting stormed on into the night, the longest meeting the Society had held to-date. Finally, they voted to return the women’s names to the Membership Committee, pending resolution of the issue by formal referendum or amendment to the constitution.

When the news reached members who hadn’t attended the meeting, most reacted in anger and disgust. Mike Angelo in Philadelphia, having urged Shermund to apply for membership, was particularly outraged: “Have we minds, or do we just run in all directions?” he wrote; “I’m embarrassed, to say the least.”

But apparently the blackballing of Terry and Shermund had not been entirely a case of surreptitious sexism lashing out anonymously where it otherwise feared to stand and be counted. Bob Dunn wrote a letter to the membership offering this explanation (in italics):

Regarding the gals, I’m for them. And I voted that way. What was so disgraceful about the last meeting [January 25]? Some of the guys who didn’t want to hurt Greg d’Alessio voted for the gals [at the meetings in November and December] when they were really against admitting them. They are guilty of trying to be kind. The three strong hands that blackballed the ladies went up to force another referendum. The three negative voters stated that they did it to bring the issue forcefully to the attention of the membership because the return on the first referendum for admitting the gals [conducted in the November Newsletter] was a mere 29 out of the entire 238 [members]. I think this time, we will get a healthy shake. So the last meeting was not in vain.

Indeed. Another referendum was conducted. This time, seventy percent of the membership voted, and two-thirds of them endorsed the idea of membership for women cartoonists. But the blackball provision of the constitution made the group hesitant to bring the candidacies they had in hand to the test of a vote. The issue was debated in meetings and investigated by committee until May.

At the May meeting, they decided to vote on the women candidates at the June meeting, and if the women were denied membership by blackball, their names would again be returned to the Membership Committee and held until a constitutional amendment could be passed to change the voting rules.

In June, women were at last formally admitted to membership in the National Cartoonists Society. Subsequent to approving Terry and Shermund, the Membership Committee had also approved Edwina Dumm, whose Cap Stubbs and Tipple, a folksy strip about a boy and his dog and his grandmother, had been warming hearts with gentle humor since 1913. All three women became members in June 1950. And no one— not even the most vociferous of the old guard male order mandarins— resigned over it. The Society had survived another test of its vitality. But it would not have happened without that wonderfully sarcastic letter from Hilda Terry.

In June, women were at last formally admitted to membership in the National Cartoonists Society. Subsequent to approving Terry and Shermund, the Membership Committee had also approved Edwina Dumm, whose Cap Stubbs and Tipple, a folksy strip about a boy and his dog and his grandmother, had been warming hearts with gentle humor since 1913. All three women became members in June 1950. And no one— not even the most vociferous of the old guard male order mandarins— resigned over it. The Society had survived another test of its vitality. But it would not have happened without that wonderfully sarcastic letter from Hilda Terry.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022