What Stan Lee REALLY did at Marvel Comics

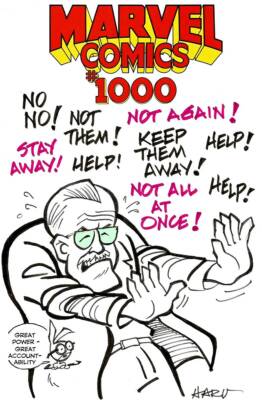

Marvel Comics’ Stan Lee, editor, publisher and comics guru, is the subject of an article in last spring’s anniversary issue of The New Yorker, a review of another in the seemingly unending parade of Stan Lee biographies; this one, True Believer by Abraham Riesman. Just for a few derisive laughs, I’ve posted my caricature of Stan Lee, adorning one of those “blank” comic book covers, this one for Marvel Comics No. 1000.

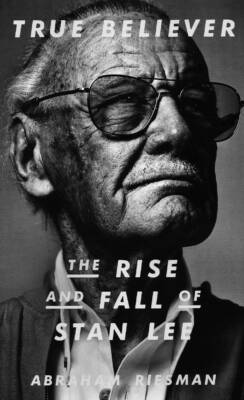

Riesman’s contribution to the cottage industry of Stan Lee biographies takes the position that Lee isn’t what he appears to be, an appearance Riesman apparently believes that Lee carefully orchestrated in a continuous effort at self-promotion and -aggrandizement (but which I, having more experience at Stan Lee than Riesman, believe to be merely the result of various accidents, which we’ll visit anon).

Riesman’s contribution to the cottage industry of Stan Lee biographies takes the position that Lee isn’t what he appears to be, an appearance Riesman apparently believes that Lee carefully orchestrated in a continuous effort at self-promotion and -aggrandizement (but which I, having more experience at Stan Lee than Riesman, believe to be merely the result of various accidents, which we’ll visit anon).

The review of Riesman’s book is conducted by Stephanie Burt, otherwise an English professor at Harvard, who, judging from her review, is apparently anxious to prove she is with it on comic books. But she stumbles occasionally.

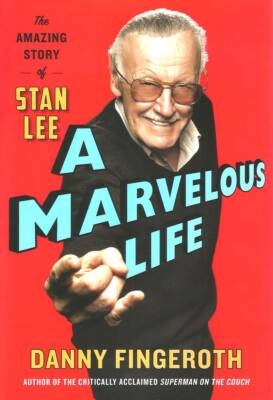

She says Riesman’s book (Crown 2021) is “the first biography completed since Lee’s death in 2018,” overlooking at least two others, both completed since Stan Lee died: Danny Fingeroth’s A Marvelous Life was published in 2019; and Liel Leibovitz’s Stan Lee: A Life in Comics, published in 2020.

Lee went to work in his uncle’s comic book company; yes, but Goodman’s publishing company produced other publications as well — pulps, as they were known, among them, Ka-Zar (a Tarzan knock-off) and Marvel Science Stories, and a title or two aimed at male readers. She says Jack Kirby was known for drawing “dynamic action and far-out costumes”; yes to the first, but probably not the second.

Eager (it seems) to show off her esoteric college-bred knowledge, she drops a couple unlikely foreign terms: kunstlerroman and stakhanovite. The first, in reference to Lee’s life working in an art form, is supposed to remind us of a story in which the hero often dreams of becoming a great artist but settles for being a merely useful citizen. The künstlerroman often ends on a note of arrogant rejection of the commonplace life.

With stakhanovite, she refers to Jack Kirby’s extremely productive life/work style, which, the term suggests, is akin that of a Soviet industrial worker awarded recognition and special privileges for output beyond production norms.

I must point out that I haven’t read Riesman’s tome yet, so my only knowledge of it comes from reading Burt’s review. And it’s difficult to tell, much of the time, whether Burt is repeating Riesman’s opinions or asserting her own in imitation of Riesman.

She is immediately hostile to Lee the creator of the Marvel universe. She begins at once belittling Lee’s achievement, suggesting strenuously that his achievement is a fiction about his prowess that was created entirely by Stan Lee.

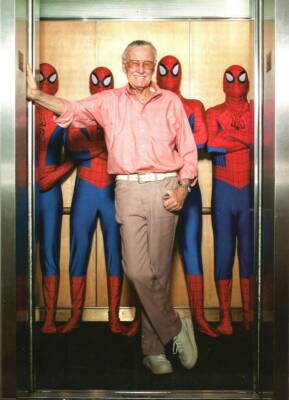

Lee, Burt insists, was “a grand self-mythologizer … He became the face of the company. No one could stop him.”

And she refers more than once to Lee’s apparent need for attention.

The talent-less Lee couldn’t do much by himself, Burt says. She acknowledges his skill at orchestrating the production of Goodman’s comic book operation, but fails to recognize that orchestration is a talent. And Lee did that by himself, giving orders to others.

She quotes comic book writer Chris Claremont (who, I assume, is quoted by Riesman), who “recalls a figure [Lee] ‘good as an editor, equally good as a manager, equally good as inspiration.’ Artists and writers whom Lee would have regarded as his juniors generally paint him in the sixties as bombastic but kind, reliable, fun to work with.”

So Lee isn’t all self-aggrandizement.

In her closing remarks, Burt backs off the posture she’s assumed for most of the article. She’s no longer hostile to Stan Lee:

“The mutant nation [X-men but also, I’d say — speaking poetically — the entire roster of Marvel superheroes] could never have been created — or even anticipated — by the fast-talking, smug, sometimes generous, and surprisingly conventional Lee. But it could never have happened without him.”

SO WHAT, EXACTLY, did Stan Lee do at Marvel Comics? He is usually credited with inventing a team of superheroes that quarreled and bickered amongst themselves, behaving, in other words, like ordinary people instead of super beings.

But that’s not what he intended to do.

In creating the Fantastic Four in November 1961, Stan Lee did not set out to invent a team of superheroes that quarreled and bickered amongst themselves. He set out to concoct a parody of superheroes. He intended to ridicule superheroes.

No one that I know of has arrived at this interpretation. Except me. Until now, Stan Lee hasn’t got away with it: nobody knew the Fantastic Four was a parody because Stan Lee was not a very good writer.

For years, he wrote slapstick comedy, making humor by punning, in Dan DeCarlo-drawn books such as My Friend Irma and other “babe books.” Corny stuff, and Stan was adept at corny. But serious comedy — parody — exceeded his ability. So the Fantastic Four wound up looking like a fresh, new kind of superheroes.

The usual story of the creation of the Fantastic Four involves Stan’s wife, Joan. According to the treasured litany, Stan was complaining to Joan about his latest assignment from Martin Goodman — to create a team of superheroes like the one just recently launched at DC Comics, the Justice League.

Stan was complaining because (as Danny Fingeroth has it) “he didn’t want to just revive the old Timely heroes.”

At this point, Joan interrupts him and tells him “(as she seems to have told him numerous times in an ongoing conversation) that he might as well try to do something different — quit complaining about being forced to churn out formulaic pap — and see what would develop. The worst that could happen is that Martin would fire him … and he’d been claiming to want to quit anyway.”

So, disliking superheroes and the formulaic pap they wallowed in, Lee decided he’d just ridicule superheroes by showing them to be flawed human beings despite their super powers. He’d write a parody. And he did.

And when readers responded to the “parody” be applauding this “fresh, new” approach — superheroes with normal, human failings — not recognizing it as parody, Stan was surprised. But he was promoter enough to recognize good thing when he saw it: he went on playing to that appreciative audience, only now he wasn’t trying to write parody. He just produced more episodes in which the Fantastic Four interrupted superhero-ing every so often to quibble amongst themselves.

If readers liked superheroes for their superhuman strength, then he’d give them unadulterated strength with the Hulk in the spring of 1962. If readers liked superheroes with feet of clay, then perhaps they’d like a teenage superhero plagued by all the usual adolescent problems of insecurity and self-doubt. So Stan created Spider-Man in the summer of 1962.

If readers liked superheroes for their superhuman strength, then he’d give them unadulterated strength with the Hulk in the spring of 1962. If readers liked superheroes with feet of clay, then perhaps they’d like a teenage superhero plagued by all the usual adolescent problems of insecurity and self-doubt. So Stan created Spider-Man in the summer of 1962.

By now, Stan was on a roll. He’d long ago given up parody. He was writing superheroes with ordinary human personalities.

And comic books about these kinds of characters were attracting the attention of the mainstream news media. And that’s where Stan stumbled.

According to Riesman (as recounted by Burt), Nat Freedland, a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune, came to the Marvel office in search of a story about these “new” superheroes. And Stan gave him a story. He demonstrated the “Marvel Method” of producing comic book stories.

Stan had been forced to develop the Marvel Method by the quantity of comic books he was committed to writing. He simply didn’t have time to produce full scripts with dialogue and stage directions in the customary manner of a movie script. So he short-cutted. He’d meet with the artist assigned to a book, and he’d suggest a topic or a storyline, discussing it briefly with the artist, both of them adding turns and twists to the story as they talked.

Then the artist would go off and draw the story, often adding new twists and ramifications as he drew. Then he’d give Stan the penciled pages, and Stan would write captions and speeches that carried the storyline, adding quips and quirks as he went.

When Freedland wrote about Stan’s demonstration of the Marvel Method, he focused on Stan’s role in the “writing” of the stories. Freedland was a writer, of course, and he understood writing; he didn’t understand drawing, so his report didn’t say much about that.

As a result, Stan emerged as the creative powerhouse at Marvel Comics. He was the star of the show.

NOW, I DOUBT THAT STAN KNEW what would be the consequences of his demonstration of the Marvel Method for Freedland. He didn’t deliberately set out to portray himself as the heart and soul, the main creative force of Marvel Comics. He didn’t deliberately leave his artist collaborators out of the process. He was just giving Freedland a story — a somewhat sensational story about how he and his artists created comic books, a story that would promote Marvel Comics.

And comics in general. Until the arrival of the Marvel universe of flawed superheroes, comic books were largely ignored by the general public — if they were not also disdained. Publicity like Freedland would produce — and that others following in his footsteps would produce — would go far towards redeeming comics as an entertainment art form.

That was the over-all purpose of Lee’s demonstration of the Marvel Method. But the demonstration had the incidental effect of portraying Stan as the initiating creative force in making Marvel Comics.

After that, he was suddenly the “face” of Marvel Comics. And he was approached by other reporters, whose reports kept repeating Stan’s role in the process until the artists didn’t seem to be contributing much to the process.

Some of the artists who had descended into anonymity in the public prints began to feel snubbed by their editor/boss. When they started to object, Stan suddenly realized what was happening, and he tried to re-insert artists into the process, naming them when talking to reporters. By then, alas, the mold was set: Stan was the man. He was the story.

But fans began to sound off, labeling Lee as an egocentric show-off who could care less for the careers and fates of the artists he worked with. And there was the example of Steve Ditko quitting (in a huff? everyone wanted to find out). And when Kirby quit, what was that about? More fed up with Stan’s self-promotion?

All of this prompted fans to do more careful research into the relationship between Lee and the artists. Careful examination showed that Lee was the victim of accidental advancement rather than the instigator of conscious plotting.

But it was too late.

In writing his book, Abraham Riesman set out to correct the record, to expose Stan Lee as a fake. He was not the sole creative force at Marvel. As I said, I haven’t read Riesman yet, but I suspect he doesn’t recognize Stan Lee’s rise as largely an accident. Instead (judging from Burt’s review), Riesman sees Stan Lee’s machinations as a deliberate attempt to get the spotlight to shine on him and him alone with Stan making a conscious attempt at self-glorification.

Although much of the publicity surrounding the publication of True Believer claims that Riesman’s treatment of Stan Lee’s professional personality is an expose of huge dimensions, it actually isn’t. Stan Lee has been unmasked by others repeatedly over the last 20-30 years. So there may not be anything new and/or earth-shaking in Riesman’s book, despite the assertions of the publicity department.

Although much of the publicity surrounding the publication of True Believer claims that Riesman’s treatment of Stan Lee’s professional personality is an expose of huge dimensions, it actually isn’t. Stan Lee has been unmasked by others repeatedly over the last 20-30 years. So there may not be anything new and/or earth-shaking in Riesman’s book, despite the assertions of the publicity department.

We’ll soon find out. Just as I was typing the foregoing, the mail arrived, and it included a copy of Riesman’s True Believer. We’re not supposed to judge a book by its cover, but if we compare Riesman’s cover to Fingeroth’s, what a difference: one cheerful and jocular; the other, grim as death. Stay ’tooned.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022