Authenticity in Western Comics

Even in make-believe, I opt for authenticity. In art, Russell over Remington, say. Admirers of western comics usually pit Remington against Russell, and, while I admire Remington, I love Russell. Frederic Remington (1861-1909), like Charlie Russell (1864-1926), was born in the East — Canton, New York, though, not St. Louis — but unlike Russell, Remington never lived in the West. He just visited there. And while visiting, he took copious notes in the form of sketches of the indigenous population which he subsequently turned into a visual record of the West, a remarkably accurate and detailed portrait, albeit focused mostly on the occupation forces (U.S. cavalry), tribal costume, and fur trapping. Not many cowboys. And Remington had never pushed cows through a frozen winter as Russell had done.

According to one of the numerous tales of Russell’s youth, he would acclimate himself to the descending temperatures in the fall of the year by putting on another shirt. Every time it got a little colder, he’d add yet another shirt to the layer on his back. Then in the spring as temperatures rose, he’d start removing the shirts, one at a time, pacing the removal to the increasing warmth. When he got down to bare skin, he took his annual bath and bought a new shirt and started all over again.

According to one of the numerous tales of Russell’s youth, he would acclimate himself to the descending temperatures in the fall of the year by putting on another shirt. Every time it got a little colder, he’d add yet another shirt to the layer on his back. Then in the spring as temperatures rose, he’d start removing the shirts, one at a time, pacing the removal to the increasing warmth. When he got down to bare skin, he took his annual bath and bought a new shirt and started all over again.

That’s cowboyin’.

Remington undoubtedly changed his clothes regularly whether he was back home in the East or making sketches out West.

In the art of the West, then — for me — Russell over Remington. And on the funnies page, Red Ryder over Hopalong Cassidy.

The gimpy trouble-prone redheaded saddlebum of Clarence Mulford’s novels about the boys at the Bar-20 ranch lost limp and all semblance of scruffiness when transformed by actor William Boyd into the black-garbed silver-haired Hoppy of the silver screen and, later, tv. The novels had a flavor of the old West; the movies, of the “new” West — that is, Hollywood.

Boyd had the perspicacity to acquire ownership of the 54 Hopalong Cassidy films he’d starred in from 1935 to 1943, and when tv kicked in all across the country, he made a fortune exhibiting the old films and the new ones he subsequently made. And in 1949, no doubt seeking diversity in merchandising options for the character, Boyd decided to take his version of Hoppy into newspaper comics.

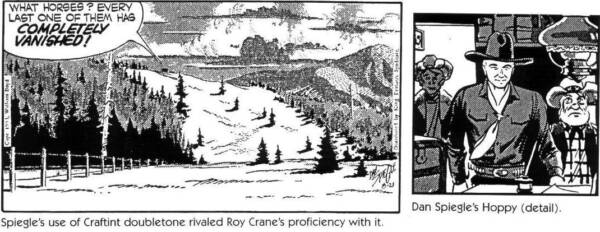

At just about this moment, a young artist and World War II Navy veteran named Dan Spiegle, having exhausted his share of the G.I. Bill with three years’ study at the Chouinard Institute of Art in Los Angeles, was hoping to sell a cowboy comic strip he’d concocted.

A chance encounter with the brother-in-law of one of Boyd’s managers led to a meeting with Boyd. As comics chronicler Mark Evanier tells it, quoting Spiegle: “I was very fortunate to find Bill Boyd in an agreeable mood, and he really liked the way I drew horses. He said it didn’t matter how I drew him — that would come with practice — but you could either draw horses or you couldn’t.”

Spiegle was soon hired, and the Hopalong Cassidy newspaper comic strip started January 4, 1950. Written at first by Dan Grayson, one of Boyd’s minions, and later by Royal King Cole, it ran until 1955, but it was Spiegle’s art that distinguished the strip. He started off good, and he got better and better. Said Evanier: “Gil Kane later called it the best-drawn western comics strip of all time.”

The Denver Post (my hometown paper) started publishing it right from the start, and although I was not yet a fan of the tv Hoppy (television didn’t arrive in Denver until a few years later, a delay caused, we all understood, by the curvature of the earth and the straightness of the video waves along which tv was broadcast in those primitive times), I was smitten with Spiegle’s artwork, its spare linear quality, the vastness of the desert horizons across which Hoppy rode, and the increasingly sophisticated use of Craftint gray tones. He achieved an almost photographic tonal gradation sometimes, occasionally even leaving off defining outlines.

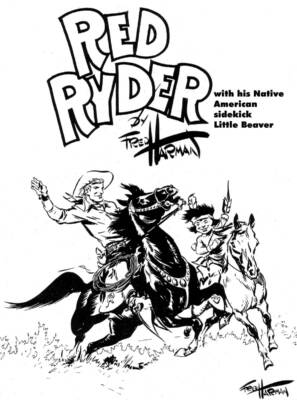

But further down the comics page in the Post was Fred Harman’s Red Ryder, and it had a knottier reality that I recognized from my own rambles through hillside stands of shaggy pine trees and straggly juniper bushes. Red wore chaps (not always but often) and looked bow-legged. And all the fences at his ranch and the boardwalks of his hometown, Rimrock, looked like real wood, weathered and warped, and the wheels on wagons almost certainly wobbled. At my first encounter with Red, I thought his jaw was too large and his shock of red hair too unruly, but I could never fault Harman for the picture of the West he drew.

But further down the comics page in the Post was Fred Harman’s Red Ryder, and it had a knottier reality that I recognized from my own rambles through hillside stands of shaggy pine trees and straggly juniper bushes. Red wore chaps (not always but often) and looked bow-legged. And all the fences at his ranch and the boardwalks of his hometown, Rimrock, looked like real wood, weathered and warped, and the wheels on wagons almost certainly wobbled. At my first encounter with Red, I thought his jaw was too large and his shock of red hair too unruly, but I could never fault Harman for the picture of the West he drew.

Harman (1902-1982) was born St. Joseph, Missouri, but his father took the family to his ranch near Pagosa Springs, Colorado, shortly thereafter, and Fred grew up on a horse. That’ll give you a real feel for the old West. The Harmans were in Kansas City for a couple years spanning World War I, and Fred returned to the big city again in 1920, learning animation with Ub Irwerks and Walt Disney at Kansas City Film Ad Company. But when Disney went to California in 1923, Harman stayed in Missouri. (His brother, Hugh, worked for Disney in California, then partnered with Rudolph Ising to produce Merrie Melodies and Happy Harmonies, a series of musically accompanied cartoons from the propitiously dubbed Harman-Ising Studio. Say it aloud.)

Harman didn’t linger in Missouri long: for the next ten years or so, he wandered through California, Iowa, Minnesota, and California again before settling near Pagosa Springs. During one of his sojourns in California, he met Will James.

“He and I had some memorable times together,” the cartoonist once recalled. Probably. By the mid-1930s when Harman met him, James was famous as a best-selling author, but he was also drinking with great determination.

In 1934, still in California, Harman began self-syndicating a comic strip called Bronc Peeler. Bronc Peeler soon acquired an Native American kid as a sidekick and slowly evolved into Red Ryder (as described in Harv’s Hindsights, August 2004 at RCHarvey.com). Set in the 1890s, Red Ryder started on Sunday, November 6, 1938 (a daily was added five months later on March 27) and eventually ran in 750 newspapers.

It was unquestionably the most popular of the newsprint Westerns: the redhead entered the cinematic log 22 times, and Harman, who returned to Pagosa Springs in 1940 and started the Red Ryder Ranch, became a Colorado celebrity and radio personality.

It was unquestionably the most popular of the newsprint Westerns: the redhead entered the cinematic log 22 times, and Harman, who returned to Pagosa Springs in 1940 and started the Red Ryder Ranch, became a Colorado celebrity and radio personality.

The Red Ryder comic book debuted with a single issue in September 1940, appeared sporadically August 1941 – December 1943, then bi-monthly until January 1946, when it began a monthly schedule until it ceased in April 1957 with No. 151. Harman reportedly drew Red’s adventures for the first 99 issues, which, in their earliest manifestations, included short comical material, a juvenile gang feature called “Kiyote Kids,” and reprints of the King of the Royal Mounted strip as well as separate stories about Red Ryder and Little Beaver. By the mid-1950s, Harman was phasing himself out of drawing the strip; in the 1960s, he took up oil painting seriously, producing scenes evocative of Russell and helping found the Cowboy Artists of America. The comic strip, produced at the end by Bob McLeod, trailed off in December 1964.

Only J.R. Williams, something of a range-riding veteran himself, could rival Harman for authentic reek. But Williams’ single-panel cartoon, Out Our Way (1921-1977), which regularly but not exclusively featured cowboying, hadn’t Harman’s graphic energy. Harman’s horses in particular were dynamos, prancing restlessly and rearing up at the slightest provocation. Williams’ weary cowpokes didn’t change their shirts all that often, I’m sure, but Harman was the old West with knotholes and bowed legs.

Harman drew with a juicy brush, splashing his drawings through the panels in a fluid, sketchy manner and drenching them in black shadow. Realistically for a Western, Red was on horseback much of the time, and Harman could make his hero sit a horse convincingly. Not having studied the situation like Harman, I can’t say with authority that horses tilt like motorcycles when cornering, but that’s the way Harman drew them, and, realistic or not, it imparted to the equestrian sequences a dramatic sense of movement, and, with that, visual excitement.

Next time, we’ll take a look at a little Western comedy and how it morphed into reality.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022