A nationally known professor returned my first paper with a devastating “C –” intoning, “Clarity, Mr. Wolf, clarity!”

I took a wanderjahre between my sophomore and junior college years to help a late uncle as a driver through Europe. I knew little about “Ben,” but an expense paid trip to virtually all of Europe was irresistible to a young person who – after reading The Sun Also Rises – wanted nothing more in life than to sit a café in Montparnasse and write something that would define his generation.

I didn’t have a clue what that might be, but I assumed that young wannabe writers had to get lost, confused, alienated (alienation was big in those existential days) before they could write something compelling.

I did quite a lot of wandering through European cities that year — Paris, Madrid, Lisbon, to name a few — and spoke little English, thinking that attuning my ear to foreign sounds and rhythms would help me become a writer.

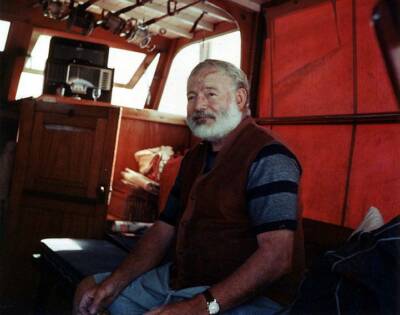

I may have been thinking of Hem in Cuba, the dialogue in Old Man and The Sea, and all the bull-fighting terminology in Death in the Afternoon, to say nothing of cojones and all around macho-lingo.

I spent a lot of time talking to myself as I walked alone and became “acquainted with the night.” This included inchoate mumbling and non-verbal imagery: making love to Catherine Deneuve, rescuing Sophia Loren from a lava flow at the base of Mt. Vesuvius, sitting next to Hemingway in Les Deux Magots as we both sharpened our pencils, he working on “Big Two-Hearted River” and I – I didn’t know, but I didn’t give up hope that words would come.

When I returned to college for my junior year, it turned out that my English needed a tuning fork. A nationally known professor returned my first paper with a devastating “C –, please come to my office.” I did: he stood facing the window, arms behind his back, voice as deep as Paul Robeson’s.

After a few harrumphs, he intoned, “Clarity, Mr. Wolf, clarity! If you break a sentence, it should bleed, Dr. Johnson, Mr. Wolf, Dr. Johnson!

I didn’t know who Dr. Johnson was, but hoped my instructor wasn’t sending me to the ER. I soon discovered, to my partial relief, that Samuel Johnson (1701-1784) was the smartest person in 18th century England and wrote, single-handed, the first English Dictionary of significance.

From that moment to the day I arrived at SUNY-Buffalo as an untenured Assistant Professor of English, I devoted myself to judicious word choice, chiseled phrases, sculpted sentences, Euclidian paragraphs.

The craggy professor’s words rang incessantly in my inner ear, “clarity, Mr. Wolf, clarity!” I sometimes thought I might need to see an ENT specialist.

But it seemed – at least for a few decades – that the old prof hadn’t given me helpful advice, even as I never wavered from his stylistic commandment.

From the moment I arrived, it became clear that clarity no longer was in fashion. The anti-war movement had been translated somehow into terms of “anti-meaning” and “protest-nonsense.”

Dr. Johnson and I were on the ropes and soon looking up at the lights. There were many poets in the department; some were writing poems like this:

…funny these tulips, inlaid with enameled

frost, guileless manipulations, altogether

benched. Target to presuppose umpteen incineration.

and:

Antique mirror

Etce ce Tera. Forgotn quiet all. Nobody grows old and crafty

here in middle air together. Long ago ice wraith foliage.

I had such fren

They called themselves LANGUAGE POETS. Some were brilliant, I was told, but I didn’t know what language they had in mind. I knew only that they were “in” and Robert Frost’s rhythm wisdom –“Somethere there is that doesn’t love a wall” –was “out” when it came to getting a raise.

The Viet Nam war ended, years passed, and many protests against it, some sincere, but absurd, went out of fashion, including the revolt against established language and traditional forms of poetry.

These poets became less fashionable and those who had taken Frost’s fork in the poetic road were now getting the raises.

Late one afternoon, a LANGUAGE poet — unshaven, thin, and stooped – came to my office. He closed the door behind him, sat down, and whispered, “This is between us, I hope, it’s somewhat embarrassing, but I need a lesson in clarity, the market’s gotten tighter.”

I helped as much as I could. At the end of the academic year, we both got raises. I thought with gratitude of the craggy prof and Frost’s line, “The tribute of the current to the source” in “West-Running Brook.”

Howard R. Wolf published a slim volume of poetry many decades ago, Upper Manhattan: A Family Album. It made total sense and sold 100 copies. “Too much clarity,” a friend explained. He began his journalistic career as a self-appointed witty columnist for the Horace Mann School Record.

- Red States in the Sunset - August 10, 2023

- A Robin Hood Rerun - July 26, 2023

- Space Exploration: In Dreams Begin Responsibilities - July 3, 2023