What’s wrong with this picture? A cartoonless New York Times gives up cartoons, and the Editooning World goes bonkers.

THE NEW YORK TIMES, which doesn’t print editorial cartoons, announced on June 10 that it wouldn’t be printing editorial cartoons, and editorial cartoonists, pitchforks and torches in hand, mobbed up the streets in protest. Does that make sense?

Well, yes. Although the Times is notorious for not printing political cartoons, it does print political cartoons in its international edition. Until July 1. After that, no more.

The Times used to publish editoons in its weekly news review section but gave that up several years ago. And that left the international edition as the Times’ sole venue for editorial cartoons.

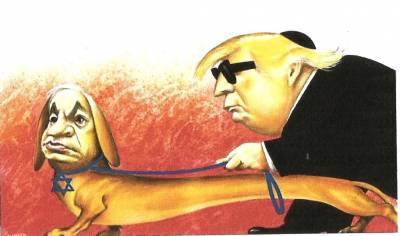

The trouble started on April 25 when the Times blundered into a hail-storm of social media protest over a cartoon in the international edition that depicted a blind President Donald Trump, wearing sunglasses and a yarmulke, being led by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who’s a guide dog with a Star of David around his neck.

The trouble started on April 25 when the Times blundered into a hail-storm of social media protest over a cartoon in the international edition that depicted a blind President Donald Trump, wearing sunglasses and a yarmulke, being led by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who’s a guide dog with a Star of David around his neck.

The watch-dogs of the world saw anti-Semitic “tropes” in the imagery: 1) Putting a yarmulke on the U.S. President in negative way. 2) Putting the face of the Prime Minister of the Jewish state on a dog. 3) Using a Star of David on the collar. 4) Implying the U.S. is ‘blindly’ led by Jews and/or Israel.

We analyze the fallacies inherent in this kind of thinking—while acknowledging the validity of the criticism—in our online magazine, Rants & Raves, Opus 392A, at RCHarvey.com. For our present purposes, we’ll return to the scandal at hand after noting that the Times issued an apology for the April 25 cartoon, admitted that the cartoon was “anti-Semitic,” and announced that it would discipline the (unnamed) editor who chose to publish the cartoon (saying he lacked “adequate oversight”), and the paper would enhance its bias training. The Times also said that it will no longer use the syndication service that supplied the cartoon.

Then came the announcement of June 10, landing like the proverbial turd in the political cartooning punch bowl.

The consequences of all this—-mostly in irrate and exasperated reaction among editoonists-—we’ll delve into at some length. In a minute. For the immediate present, we’ll plunge instead into—:

WAIT—WHAT?

A Tempest, Perhaps, in a Teapot?

Amid all the sturm und drang over the New York Times’ dropping its editorial cartoons are two factoids sometimes overlooked in the excitement. First, the loss at the Times is in the international edition of the paper not the domestic edition, the one we all read (or used to). Not worth making a fuss over? In these times with staff editoonist jobs falling away, left and right, any diminution of the role of the editorial cartoon is worth getting worked up about. And so a lot of editoonists did just that.

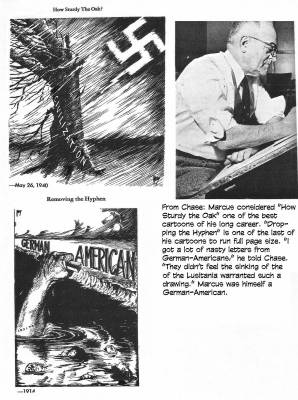

The second factoid: the domestic edition of the Times hasn’t had a regular editorial cartoon since 1958 when Edwin Marcus retired after 50 years on the job.

These days, it is generally supposed that the Times has never had a staff editoonist. That may be because most of those making the claim weren’t even born in time to see Marcus’ farewell cartoon. Or they were too young to know what an editorial page looked like let alone an editorial cartoon.

For those who think the Times has never had an editorial cartoon, we must pause at Marcus. He became the paper’s editoonist in 1908, succeeding Hy Mayer, who was the first Times editoonist. So in the history of the Times, it had at least two editorial cartoonists.

Marcus had a talent for getting likenesses, they said, and before World War I, his cartoon appeared full page on the first page of the paper’s drama section. Full page! Probably, however, not what we’d call an editorial cartoon these days. More like Al Hirschfeld maybe.

“I got to know all the stars of the theatre,” Marcus told John Chase, who was putting together a book about American editorial cartoonists, Today’s Cartoon (1962).

“Will Rogers and Flo Siegfeld were my closest friends,” Marcus continued. “I did the Bull Durham ad drawings for all Will’s quips, and spend hours with Ziegfeld laying out his display pages. After twenty-five years, the dramatic page drawings began to interfere with the cartoon, and the office let me drop it.”

Photographs took the place of Marcus’ pictures.

For almost all of the fifty years of his career, Chase reports, Marcus worked at home. “Weekly, he made two trips down to the Times—Thursday mornings with about a dozen roughs to show his editor, and Fridays to turn in his finished cartoon.”

For almost all of the fifty years of his career, Chase reports, Marcus worked at home. “Weekly, he made two trips down to the Times—Thursday mornings with about a dozen roughs to show his editor, and Fridays to turn in his finished cartoon.”

So the Times’ longest tenured editoonist drew only one cartoon a week.

Still, he was on staff and he did editorial cartoons. So the Times did, indeed, have an editorial cartoonist at one time, and a long time it was.

When asked why he had never been replaced following his retirement, Marcus told Chase, “the editor said something about my being ‘an institution.’”

Yes. After fifty years, an institution.

And now, sixty-one years since Marcus left, it’s time to re-institute the institution. The teapot is boiling dry.

Taking Up Where We Left Off Several Hundred Words Ago

Editoonist Patrick Chappette was the first to react to the Times announcement that it was giving up on editorial cartoons: on June 10 at his blog, he traced his career as a crusade to get the Times to publish editorial cartoons:

“In 1995, at twenty-something, I moved to New York with a crazy dream: I would convince the New York Times to have political cartoons. An art director told me: ‘We never had political cartoons and we will never have any.’”

So Chappette started his one-man campaign to change the Times.

“For years, I did illustrations for Times’ Opinion and Book Review, then I persuaded the Paris-based International Herald Tribune (a NYT-Washington Post joint venture) to hire an in-house editorial cartoonist. By 2013, when the NYT had fully incorporated the IHT, there I was— featured on the NYT website, on its social media and in its international print editions. “

Denied entrance through the front door, Chappette snuck in through the rear window. He had proven the art director wrong: “The New York Times did have in-house political cartoons. For a while in history, they dared.”

Then came the June 10 announcement.

But it wasn’t just about cartoons, Chappette maintained, “but about journalism and opinion in general. We are in a world where moralistic mobs gather on social media and rise like a storm, falling upon newsrooms in an overwhelming blow. This requires immediate counter-measures by publishers, leaving no room for ponderation or meaningful discussions. Twitter is a place for furor, not debate. The most outraged voices tend to define the conversation, and the angry crowd follows in…

“Along with The Economist (featuring the excellent KAL), the New York Times was one of the last venues for international political cartooning. For a U.S. newspaper aiming to have a meaningful impact worldwide, it made sense. Cartoons can jump over borders. Who will show the emperor Erdogan that he has no clothes, when Turkish cartoonists can’t do it ? (One of them, our friend Musa Kart, is now in jail.) Cartoonists from Venezuela, Nicaragua and Russia were forced into exile. Over the last years, some of the very best cartoonists in the U.S., like Nick Anderson and Rob Rogers, lost their positions because their publishers found their work too critical of Trump. Maybe we should start worrying. And pushing back. Political cartoons were born with democracy. And they are challenged when freedom is.”

“I THINK THE MESSAGE that’s being sent by the Times is that they’re spineless and really can’t take the heat,” Matt Wuerker told The Daily Beast. “This whole episode started out with the anti-Semitic cartoon that slipped through their editorial side and created that shit storm. I find the whole thing kind of tragic and a little bit pathetic.”

Speaking to the larger landscape, Wuerker, the Pulitzer-winning cartoonist for Politico, said: “The collapsing space for political cartoons and satirical commentary because editors don’t have the spine to stand up to social-media outrage campaigns is bad for free speech, and bad because political debate benefits from a little humor now and again.”

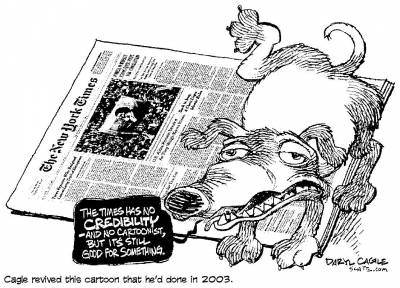

Taking a similar view on the bigger issue is Daryl Cagle, head of the syndicate Cagle Cartoons, which distributes Chappatte’s work to about 800 subscribing clients.

“By choosing not to print editorial cartoons in the future, the Times can be sure that their editors will never again make a poor cartoon choice,” Cagle said. “Editors at the Times have also made poor choices of words in the past. I would suggest that the Times should also choose not to print words in the future — just to be on the safe side.”

“By choosing not to print editorial cartoons in the future, the Times can be sure that their editors will never again make a poor cartoon choice,” Cagle said. “Editors at the Times have also made poor choices of words in the past. I would suggest that the Times should also choose not to print words in the future — just to be on the safe side.”

John Adcock, who cartoons in the United Kingdom for the Independent, may be a long way away, but he sees clearly: “The paper has said the offending cartoon was published due to a weak editorial process. The fear is that the threat of greater online outrage in the future encouraged them to think the only solution was to remove the process altogether. Taking the path of least resistance and giving in to those voices means damaging this unique form of journalism and therefore damaging free speech, a pillar of our democracy.

“Political cartooning,” he continued, “has always been a difficult and precarious way to make a living and most cartoonists will be aware of the ups and downs of pursuing this unusual career. But when a cartoonist’s position is cut due to editorial timidity or simply a lack of understanding of the power and importance of this art form, then it’s a sad day for anyone who gives a damn about holding the powerful to account.”

“Exactly,” Chappette agreed. “And this sends a signal discarding a whole genre that is so rooted in the history and tradition of democracy… But we must stop being afraid of offended people because the whole controversy that was triggered a month ago by that cartoon, I think it should have encouraged a discussion, explaining why this cartoon was wrong, how it’s run, what is cartooning, and there was no space for that. I think the New York Times had to deal with a huge storm triggered by social media. We need to be able to withstand this and to go back to putting things into perspective.”

CARTOONIST ORGANIZATIONS leaped to the barricades to defend their genre and protest the Times’ decision. Writing for the Board of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, AAEC president Kevin Siers said: “Doubling down on its clumsiness in response to the resultant furor [over the anti-Semitic cartoon], the Times announced that they would no longer run syndicated editorial cartoons. Their decision now to not run in-house cartoons as well only adds to that ham-handedness, blaming the medium of cartoons for what resulted from their own lack of editorial oversight.

“In a statement defending their action, the Times said they ‘plan to continue investing in forms of Opinion journalism, including visual journalism, that express nuance, complexity and strong voice …’ From this description, it seems the type of ‘visual journalism’ the Times envisions has more to do with storytelling than with expressing strong opinions.

“The best editorial cartoons are not celebrated for their nuance. It is their clarity and pointedness, the sharpness of their satire, that make them such powerful vehicles for expressing opinion. There is no ‘on the other hand’ in an editorial cartoon. This power, understandably, makes editors nervous, but to completely discontinue their use is letting anxiety slide into cowardice. With their decision to end using editorial cartoons, the Gray Lady, as the Times has been called, has become even more gray and dingy. And the environment for free expression and the free exchange of ideas has become even more bleak.”

OTHER ORGANIZATIONS CHIMED IN. From the National Cartoonists Society’s president Jason Chatfield, we have this:

“On behalf of the membership of the National Cartoonists Society, the NCS board express our great dismay at the decision to cease running daily editorial cartoons in all international editions of the New York Times as of July 1 as they have also done for the domestic edition.”

Pointing to the long history of editorial cartooning as “an invaluable form of pointed critique,” Chatfield continued: “We find ourselves in a critical time in history when political insight is needed more than ever, yet we see more and more cartoonists vanishing from the pages of our publications. If we are to dull the voices of our most valued critics, satirists, and artists, we stand to lose much more than the ability to debate and converse: we lose our ability to grow as a society. We rob future generations of their opportunity to learn from our mistakes.”

Chatfield concluded by imploring the Times to reconsider and to reinstate editorial cartoons “to both the domestic and international editions of the New York Times in print and online.”

Chief executive officer of PEN America (Poets, Essayists and Novelists) Suzanne Nossel released a statement, hoping the Times would reconsider and adding:

“If outlets like the New York Times retreat from this uniquely potent form of political commentary, it may hasten the death of a form that has contributed immensely to our political conversation over time. The possibility of offense must not be reason to shut down valued channels of speech. As a leader in media, the New York Times can get this right and help us to see how cartoons can continue to provide insight and inspiration amid our shared global commitment to eradicating bigotry.”

The Knife-Twist of Accountability

THE WEEK magazine publishes a weekly round-up of editorial cartoons and its cover of every issue is always a full-color, painted editorial cartoon. The magazine editorialized at length:

THE WEEK magazine publishes a weekly round-up of editorial cartoons and its cover of every issue is always a full-color, painted editorial cartoon. The magazine editorialized at length:

“The incident at the Times is only the latest reason to feel concern about the state of political cartoons in this country. Once a deeply-ingrained part of American journalism, there were some 2,000 working editorial cartoonists at the start of the 20th century. In a 2012 special report by the Herb Block Foundation (named for the legendary cartoonist who coined the term ‘McCarthyism’), fewer than 40 staff cartoonists were found to be employed by U.S. newspapers, a number that is no doubt smaller today. [These numbers, often summoned up as knee-jerk reaction to whatever threatens the profession of editorial cartooning, are most probably exaggerated; we’ll explain at the end of the New York Times disquisition.]

“Editorial cartoons’ courting of controversy is often a positive and democratizing force, one that rightfully makes people in power squirm by casting motives into sharp relief. It can also come at great risk to the artists: most famously, 12 people were killed in 2015 when terrorists opened fire on the newsroom of the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, ostensibly over the paper’s cartoonish depiction of Muhammad.

“This can come with a negative side too, as it’s not totally uncommon for hateful images to make it into print in the guise of political cartoons [as the Netanyahu/Trump cartoon demonstrates]… Still, such mistakes, while deeply regrettable, should not cloud the important work that many other cartoonists do.

“This can come with a negative side too, as it’s not totally uncommon for hateful images to make it into print in the guise of political cartoons [as the Netanyahu/Trump cartoon demonstrates]… Still, such mistakes, while deeply regrettable, should not cloud the important work that many other cartoonists do.

“A truly great editorial cartoon, rather, should be the knife-twist of accountability. While reported [verbal] articles keep the powers that be in check, and opinion and editorial sections help readers make sense of that reporting, editorial cartoons are the jolt that shocks you into caring. Many people find them so vital to the journalistic process that there are calls to put them on the front page [where editorial cartoons once reigned in almost every paper].

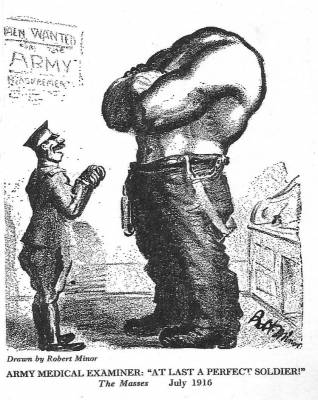

“To lose them, then, is to lose one of the most powerful wakeup calls we have available to us as readers. Where would we be without Robert Minor’s succinct anti-war illustration of a headless man, declared by an army medical examiner to ‘at last’ be ‘a perfect soldier’? Or without Benjamin Franklin’s dissected snake urging the states to “join, or die,” often cited as America’s first political cartoon and a pivotal rallying cry ahead of the Revolutionary War? Or Pia Guerra’s chilling picture of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School security guard Aaron Feis being welcomed into the afterlife by countless victims of mass shootings.

“Still, there is a worrying drought of editorial cartoonists, and the Times’ move this week is the wrong one, regardless of whether it was truly long in the making or a knee-jerk response to an unfortunate event. As cartoonist Ted Rall told NPR in 2008, the members of his profession are “the canaries in the coal mine” for the newspaper industry and, in turn, for the state of American democracy.

“Still, there is a worrying drought of editorial cartoonists, and the Times’ move this week is the wrong one, regardless of whether it was truly long in the making or a knee-jerk response to an unfortunate event. As cartoonist Ted Rall told NPR in 2008, the members of his profession are “the canaries in the coal mine” for the newspaper industry and, in turn, for the state of American democracy.

THE CHORUS OF REACTION to the Times’ cowardly decision (a bean-counter’s decision, we might say, something those concerned only with bottom lines can make with equanimity) continued for the better part of a week.

Critics of the Times continued to blast the paper throughout the week. “Feeble,” “weak,” “spineless,” and “cowardly,” appeared more than once. “Chickenshit” also proved popular.

Editoonist Walt Carr found the Times’ decision “not only disappointing but disturbing. ‘Gore the ox’ single-panel cartoons have been around since ink first kissed paper. Visual commentary and satire have always been an asset to newspapers and their readership. The exposure of hypocrisy in our times is needed more now than ever with the miscreant currently in the White House. The decision snacks of cowardice and a victory for said miscreant.”

CNN anchor Jake Tapper (who regularly features his own political cartooning on his Sunday public affairs show, “State of the Union”), blasted the Times’ move as “just one more nail in the coffin of what is a struggling art form, given how corporate American has taken over local newspapers and gutted the industry. … It’s regrettable that at this time when journalists are under fire literally and figuratively that more newspapers aren’t doing everything they can to support editorial cartoonists.”

In a subsequent email exchange, Tapper elaborated: “The Times should be a leader for editorial cartooning, it should blaze a trail for other newspapers to follow, as it does in so many other ways. … Other media organizations look to her to assess how to behave. … I would love for editors to lead the way and not only reverse this decision internationally but domestically as well.”

“It’s completely chickenshit and cowardly,” said Joel Pett, the Pulitzer-honored editorial cartoonist for Kentucky’s Lexington Herald-Leader. “Honestly, I think it’s a disgrace.”

Kevin “KAL” Kalaugher, long-time editoonist for the Baltimore Sun and The Economist, said: “When I travel around the world addressing audiences about satire and freedom of expression, nothing impresses listeners more than America’s embrace of cartoons. We can savage our leaders in caricature without danger of official reprisals. Unfortunately, today in America, the danger to cartooning comes not from angry tyrants before us but from our very own newspapers cutting our knees out from behind.”

Ann Telnaes at the Washington Post called the Times’ decision to drop all editorial cartoons “another body blow to the profession of editorial cartooning. While several of my colleagues from around the world have been imprisoned by autocratic leaders over their work, American editorial cartoonists are protected by our First Amendment from governments looking to silence uncomfortable truths. Unfortunately, that protection doesn’t extend to publications that don’t understand the historical significance of editorial cartoons and their essential role in a free press.

“It’s easy to casually dismiss these ‘cartoons,’” she went on, “—after all, just the word cartoon brings up images of reading the comics pages or watching Saturday morning television. But an editorial cartoon is much more than a humorous image. Cartoonists have been threatened, imprisoned and even killed for drawing cartoons criticizing powerful people and institutions. Daumier, Gillray, Nast, Herblock, Mauldin, Conrad and Oliphant all created powerful visuals that were part of the political debate of their times.”

ROB ROGERS, fired by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette a year ago for doing too many cartoons unfavorable about the Trumpet (and they were not only unfavorable, they were strongly, unflinchingly critical and, hence, decidedly anti-Trump), invoked history and the profession’s first powerful practitioner:

ROB ROGERS, fired by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette a year ago for doing too many cartoons unfavorable about the Trumpet (and they were not only unfavorable, they were strongly, unflinchingly critical and, hence, decidedly anti-Trump), invoked history and the profession’s first powerful practitioner:

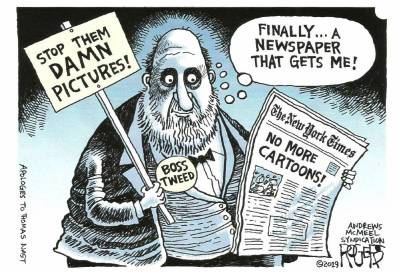

“Stop them damn pictures! I don’t care what the papers write about me. My constituents can’t read. But, damn it, they can see the pictures!”

That’s a quote from William M. Tweed from around 1875 and it speaks to the importance of the role of editorial cartoons.

Tweed, referred to as “Boss” Tweed, controlled Tammany Hall, the Democratic seat of political power in New York City at the time. Corruption and crime were a way of life for Tweed and his cronies. Thomas Nast was working as a political cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly and constantly targeted Tweed and his ring.

Eventually, Tweed was arrested and went to prison. He escaped and fled to Spain where he worked as a common seaman on a Spanish ship. Tweed was recognized because of Nast’s famous caricature of the politician [and he was arrested and] extradited and returned to prison [in the U.S.] where he later died. The “damn pictures” quote illustrates the power of an editorial cartoon and reminds us of the importance of satire in holding the powerful to account.

IN THE INTEREST OF DUBIOUS FAIR PLAY, we’ll give Times editorial page editor James Bennett a chance to defend himself. We’ll start with the announcement that caused all the furor. As others have observed, it seems worded as if to dispel any direct connection between the anti-Semitic cartoon fallout and the discontinuing all political cartoons:

“We’re very grateful for and proud of the work Patrick Chappatte and Henr Kim Song have done for the international edition of the New York Times, which circulates overseas; however, for well over a year, we have been considering bringing that edition in line with the domestic paper by ending daily political cartoons and will do so beginning on July 1st. We plan to combine investing in forms of opinion journalism, including visual journalism, that express nuance, complexity and strong voice from a diversity of viewpoints across all of our platforms.”

Bennett flatly denied that the decision was a response to the Netanyahu outbursts.

“I can tell you this: We’ve been talking about making this move for a long time,” he said. “Once we decided not to do syndicated cartoons [in the wake of the Netanyahu gaffe], it seemed like a logical step to make this move as well. That’s the truth.”

Bennet rejected the claim by several cartoonists that if indeed his decision was unconnected to the previous uproar, he could have waited longer to execute it.

“That’s like an appearance and PR strategy,” he scoffed. “We need to do what’s right for our readers, and that’s why we’re doing this.”

Bennet, who noted that during his tenure the Times won its first Pulitzer ever for editorial cartooning—for a 2017 graphic novel-like presentation of a Syrian refugee family’s new life in America—argued: “We have been very strong in visual opinion journalism, including graphics and video. The budget is not unlimited. This is part of a broader shift away from work that’s really reactive to work like the Syrian [Pulitzer-winning] cartoons that is more enterprising.”

He continued: “We think that serves more of our readers and can have more impact toward the good in the world. … So to say we’re not interested in championing excellent work in this field, I think, is belied by our own record.”

Bennet bristled at the accusation that his decision is evidence of “spinelessness.”

“You can reach your own judgment if you think there’s a pattern of spinelessness here,” said Bennet, who has taken flak for hiring—and resisted calls for the firing of—such incendiary columnists as conservative Bret Stephens and Bari Weiss, and absorbed a barrage of incoming brickbats for devoting the entire editorial page to letters from Trump supporters. “I think that’s preposterous.”

The New York Times has a long history of hostility towards editorial cartoons. The late A.M. “Abe” Rosenthal—a domineering Times editor who was managing editor and executive editor for most of the ’70s and ’80s—was known to believe that political cartoons had no place in his newspaper because they could not be edited.

AT THE NATION, Jeet Heer has a few cogent paragraphs to say on our subject; let’s let him do it—:

Times editorial page editor James Bennet, also speaking to The Daily Beast, denies that the move was an outgrowth of the Netanyahu cartoon (although, inconsistently, he admits that canceling the subscription service sped up the decision to let go of Chappatte and Heng). Bennet maintains that he’s been thinking of axing cartoons from the paper for more than a year. If so, that makes Bennet and the Times look worse, since this was not an individual act of poltroonery but a more systematic aversion to visual satire…

In truth, the Times has long viewed editorial cartoons with sniffy disdain. For most of its existence [not quite; revisit Teapot Tempest above], the Times, along with the Wall Street Journal, was one of the few newspapers that ran no cartoons at all. In the golden age of political cartooning, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch had Bill Mauldin, the Washington Post had Herblock, the Village Voice had Jules Feiffer [whose cartoon was not quite an editorial cartoon during this period], and the New York Times had nobody…

As former Nation publisher Victor Navasky notes in his 2013 book The Art of Controversy, editorial cartoons have power to upset people that words rarely match. As a visual form, cartoons travel at the speed of light, whereas a speech travels at the speed of sound and written words are slowed down by the effort of the eye to riddle them out. As you plod word by word through this sentence, you can’t untangle the full meaning until you reach the end. By contrast, a cartoon hits you like a punch in the eye.

The element of caricature inherent in cartoons makes them even more dangerous. In intent, a cartoon is closer to a burnt effigy or a voodoo doll than it is to a reasoned essay. The goal is to wound—and that purpose is often achieved. … Hitler raved and frothed at David Low’s cartoons, earning Low a place on the hit list of those to be assassinated after the conquest of Britain was achieved.

AT POLITICO, Jack Shafer sounded the alarm, saying we are now in “The End Times of the Political Cartoon.”

“When you think about it,” he wrote, “it’s a miracle that newspaper editors ever hired cartoonists in the first place. To do their job well, they require a great deal of autonomy. And if there’s one thing editors don’t like to dole out, it’s autonomy, Chris Lamb notes in his book Drawn to Extremes: The Use and Abuse of Editorial Cartoons.

“Lamb uses a quip from former New York Times Executive Editor Max Frankel to explain why editors have abandoned their cartoonists. “The problem with editorial cartoonists is that you can’t edit them,” Frankel said.

“Obviously, you can edit cartoonists by telling them to change the captions or to draw the president in a more flattering or less flattering light. But in practice, Frankel is right. Editing a cartoonist is a little like trying to edit a song. You can order a million changes in the song, but unless you’re a songwriter those changes aren’t likely to improve the tune. (“Writers grow up to be editors,” cartoonist Mike Peters once said. “Cartoonists just grow up to be old cartoonists.”)

“Once upon a time, there were more editors willing to give cartoonists the latitude they needed to make great work, but nowadays, too many editors find it easier and cheaper to pick a safe one from a pile of syndicated drawings than employ a cartoonist. As Lamb conveys in his book, cartoonists require a greater level of independence than other newsroom hands, and fewer and fewer editors seem willing to grant that power these days.

“Like opera, jazz and poetry, editorial cartooning has become a niche art form, its greatness anchored in the past. It’s a shame we have to turn the page.

PERHAPS THE BEST SUMMARY of the whole extravaganza is given by someone whose distance from the fray might provide a less clamorous and therefore more objective perspective.

Martin Rowson is a British editorial cartoonist and writer. His genre is political satire and his style is scathing and graphic, St. Wikipedia asserts. He characterizes his work as “visual journalism.” His cartoons appear frequently in The Guardian and the Daily Mirror. He also contributes freelance cartoons to other publications, such as Tribune, Index on Censorship and the Morning Star. He is chair of the British Cartoonists’ Association. Here’s some of his response to the tragedy lurking in the Times’ decision:

“Just like any other commercial enterprise, the New York Times can do what it likes, and I look forward to seeing some scathingly satirical tie-dyes in the pages of its international edition.

“But this cuts deeper than an over-reaction to an ill-judged cartoon. Cartoons have been the rude, taunting part of political commentary in countries around the world for centuries, and enhance newspapers globally and across the political spectrum, in countries from the most tolerant liberal democracies to the most vicious totalitarian tyrannies. As we all know, they consequently have the power to shock and offend. That, largely, is what they’re there for, as a kind of dark, sympathetic magic masquerading as a joke.

“That’s also why the Turkish cartoonist Musa Kart is in jail, why the Malaysian cartoonist Zunar was facing 43 years imprisonment for sedition until a change of government last year; why five cartoonists [and seven staff members] were murdered in the offices of Charlie Hebdo in January 2015; why dozens of British cartoonists – including William Heath Robinson – were on the Gestapo death list. And why, for that matter, when in the late 1950s the London Evening Standard ran a cartoon by its Jewish cartoonist Vicky attacking the death penalty, this so shocked and outraged a GP in Harrow that he wrote to the paper regretting that Vicky and his family had escaped the Nazis.

“As Kart said at his trial, cartoonists are like canaries in the coal mine – when they come for us, you know the politics is getting toxic. But we’re not just subject to the shallow vanity of tyrants or the fury of mobs.

“The greatest threat to cartoonists has always been the very newspapers we parasitise on.

“When the accountants moved in on the U.S. newspaper industry in the 2000s, the first employees to go were the cartoonists, just like most newspapers that get closed down aren’t shut by governments but by their proprietors.

“Nor is it just money. I’ve been ‘let go’ more times than I can count (the worst case was when the [London] Times sacked me to make more room for Julie Burchill’s column, though in a previous incarnation on The Guardian’s personal finance pages in the 1980s, I was redesigned off the page and replaced with what was charmingly called ‘a creative use of white space’).

“We are, in short, expendable.

“Nonetheless, the New York Times’ decision is particularly irksome in its intoxicating combination of cowardice, pomposity, over-reaction and hypocrisy.

April is the cruelest month for the New York Times, as its much vaunted (and self-promoting) claim to be America’s “newspaper of record” was dealt an almost fatal blow when it was revealed in April 2003 that its star reporter Jayson Blair was a serial plagiarist who had fabricated many of his stories.

“You’ll note, however, that the paper did not stop using reporters altogether in order to rebuild its reputation. Nor did it issue a statement announcing that it would ‘continue investing in forms of news journalism, including textual journalism, that express nuance, complexity and strong voice from a diversity of viewpoints’ and then fill its pages with copy from, say, accountants and astrologers.

“Although after the dumbness of this decision, just give it time.”

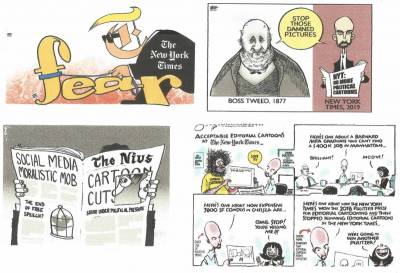

WE CONCLUDE THIS EXHAUSTIVE EXPEDITION into verbal harangue with some pictures (and a few more words) in the same vein. At the upper left is a stunner by a cartoonist whose name I lost track of, alas and alack. With simple visual invocation of symbols, he’s made the imagery of that April editoon that allegedly started all this into a visual condemnation of the Times decision: just as Netanyahu was leading Trump in the original offender, so is “fear” leading the Times. Nicely done, very. Next around the clock is Jose Neves invoking Boss Tweed, the original objector to cartoons in New York newspapers, and comparing James Bennett to him. Without Bennett’s distinctive bald head he wouldn’t be anywhere recognizable in Jack Ohman’s cartoon, next in our round.

WE CONCLUDE THIS EXHAUSTIVE EXPEDITION into verbal harangue with some pictures (and a few more words) in the same vein. At the upper left is a stunner by a cartoonist whose name I lost track of, alas and alack. With simple visual invocation of symbols, he’s made the imagery of that April editoon that allegedly started all this into a visual condemnation of the Times decision: just as Netanyahu was leading Trump in the original offender, so is “fear” leading the Times. Nicely done, very. Next around the clock is Jose Neves invoking Boss Tweed, the original objector to cartoons in New York newspapers, and comparing James Bennett to him. Without Bennett’s distinctive bald head he wouldn’t be anywhere recognizable in Jack Ohman’s cartoon, next in our round.

Ohman deploys a comic strip format in order to permit Bennett and his minions to react repeatedly to a series of cartoons. You don’t need to read the lettering (in case you can’t) to realize that the cartoons that prompt ecstasy among Bennett’s staffers are empty, nearly blank pieces of paper. The last cartoon from Dario Castellsejos offers a newspaper reader just discovering a conspicuous hole where the editoon used to be in his newspaper. The hole conveys nothing—no news, no facts, no opinion. Nothing.

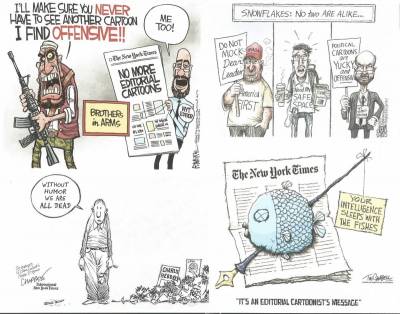

In our next exhibit, Rick McKee gets things off to a over-heated start by comparing bald but bearded Bennett to a terrorist because both tend to find cartoons offensive (enough so that, you’ll remember, a band of holligan Islamists killed 12 staff members at France’s Charlie Hebdo offices in January 2015).

In our next exhibit, Rick McKee gets things off to a over-heated start by comparing bald but bearded Bennett to a terrorist because both tend to find cartoons offensive (enough so that, you’ll remember, a band of holligan Islamists killed 12 staff members at France’s Charlie Hebdo offices in January 2015).

Next, Adam Zyglis compares three “snowflakes” (by which we have denominated the Extra Sensitive among us), the last of whom is bearded bald Bennett.

Then comes Tim Campbell whose message is simple name-calling but inventively done with a dead fish carrying the sign, the fish suggesting that all the Times is good for is wrapping dead fish, a classic description of what newspapers do. Finally, the cartoon that Patrick Chappatte drew just after the Charlie Hebdo attacks, which was published on the front page of the Times website; he’s revived it now because its message seems to apply to the Bennett/Times situation (and it reminds him of his past success with the Times).

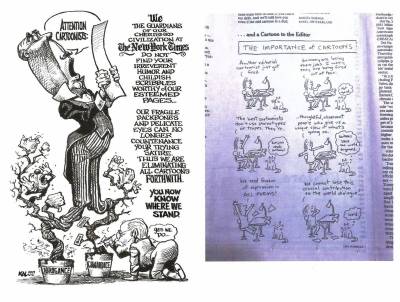

Two giant cartoons dominate our last visual aid. On the left is KAL’s, a large outgrowth of bramble bush representing the guardians of civilization (i.e., the Times) which plant, after claiming “delicate eyes,” eliminates cartoons “forthwith,” finishing by asserting that “you know where we stand.” At the bottom, KAL kneels before the pots out of which the plant grows, and we see that he is labeling them “Arrogance” and “Cowardice,” at the root of the Times’ decision.

Two giant cartoons dominate our last visual aid. On the left is KAL’s, a large outgrowth of bramble bush representing the guardians of civilization (i.e., the Times) which plant, after claiming “delicate eyes,” eliminates cartoons “forthwith,” finishing by asserting that “you know where we stand.” At the bottom, KAL kneels before the pots out of which the plant grows, and we see that he is labeling them “Arrogance” and “Cowardice,” at the root of the Times’ decision.

On the right is a cartoon that the Times printed—as a letter (“cartoon”) to the editor. It is, doubtless, the last cartoon the Times intends ever to print. The cartoon, by Liza Donnelly, shows the cartoonist at her drawingboard expounding on the editoonist dilemma and extolling the virtue of freedom of expression, a “crucial contribution to the world dialogue.” And she takes six panels to come to this vapid conclusion, expressed in uninspired ordinary language.

Compared to the editoons we’ve just seen about the Times’ attitude toward freedom of expression by cartoonists, Donnelly’s cartoon is rampant blandness—which I’m sure she intended as an ironic example of the sort of lifeless cartooning the paper undoubtedly favors. She’s just giving it what it seems to want.

ABOUT THOSE 2,000 EDITOONISTS

Who Worked in American Newspapers A Hundred Years Ago

If there were 2,000 editoonists at the beginning of the 20th century, they were not full-time editorial cartoonists. They were “staff artists/cartoonists,” some of whom occasionally drew an editorial cartoon but they mostly drew other stuff—like borders around photographs, f’instance.

So where does the number 2,000 come from?

From the number of newspapers in the country.

Edwin Emery in his definitive history of American newspaper journalism, The Press and America, says that “the years 1910 to 1914 mark the high point in numbers of newspapers published in the United States. The census of 1910 reported 2,600 daily publications of all types, of which 2,200 were English-language newspapers of general circulation.”

That’s where the number comes from. Two thousand two hundred, 2,200.

If a newspaper was financially healthy enough to publish daily, it had resources sufficient for hiring artists (at least one) some of whom could draw cartoons, And some of them did, on occasion, as I just said a paragraph ago. And some of those cartoons, sometimes, were political in intent. (Some were not: some were just funny.)

But to claim that because a newspaper artist occasionally drew an editorial cartoon he/she was an “editorial cartoonist” in the common use of the term today—that’s fudging of the highest altitude.

If doing an occasional editoon qualified an artist as an editorial cartoonist, then we have a whole lot more than a couple dozen editorial cartoonists today.

But that’s not how we’ve been counting. We’ve been counting only full-time staff editorial cartoonists. They have to be full-time, and they have to be on the paper’s payroll and come to work every day and draw the usual health benefits.

Most of those who are doing the counting agree that there are definitely 29 cartoonists who are full-time staff political cartoonists. Then, depending upon various other qualifiers (freelance full-time, enough to make a living at it, on contract but not drawing benefits, etc.), there might be as many as 48.

People like Ann Telnaes (on contract to the Washington Post), Daryl Cagle (who editoons and also runs his own editoon syndicate), Mark Fiore (who recently signed on with a newspaper to do both animations and statics; he’s not “on staff,” but he’s fully employed), and others of the same ilk.

But let’s beware: this way lies the 2,000 editoonists of 1910; and we don’t want to go there.

Still, we’re probably safe in saying that editoonists today number somewhere between 29 and 48. That’s more than 25, but it’s a lot less than 101, which is were the head count stood in May 2008, merely eleven years ago.

The withering away has been drastic.

And there’s no question that the species is endangered and moving rapidly towards extinction.

But let’s at least keep the numbers right.

ONE MORE THING…

Editorial Cartooning, a book published in 1949, values the journalistic function of editooning. It was written by Dick Spencer III (1921 – 1989), a graduate of the University of Iowa with a degree in Journalism. Following World War II, he was a staff member at Look magazine and later was an instructor of magazine production and editorial cartooning. For most of his life, he was publisher of Western Horseman magazine.

Spencer’s book about editorial cartooning is not so much a history of the species as it is a how-to book (How A Cartoonist Works, Aids to the Trade, Pen Points for Poniards), but the last chapter dwells for a few pages on the extraordinary and unexpected outcome of the 1948 Presidential Election—which Harry Truman, the incumbent, won over Thomas Dewey, who everyone expected to win. The editors of the (Washington D.C.) Star realized that this election would go down in history as one of our greatest political surprises, and they sought to memorialize the occasion by publishing a book of the editoons of their staff cartoonists, The Campaign of ’48 in Star Cartoons.

“The introductory text explained the significance and purpose of the book,” writes Spencer, “and is worthy of reprinting here.” And so he reprints it; and we do, too (in italics):

A cartoonist is many things to many men. To some he is a clown, tickling the world with the point of his pen. To others, he is a wit, drafting cogent comment on the course of events, coming through on deadline with the day’s perfectly incisive remark. To still others, he is a sort of intellectual gadfly, stinging sinners to repentance with a barb of ridicule. But if he is true to himself, he also is a reporter in the finest sense of the word, telling the story day by day with maximum economy,clarity and truth.

The Star presents here the story of this election year,as told in the daily work of its three cartoonists (Clifford Berryman, his son Jim, and Gib Crockett)…

These pages will remind you of things you want to remember about the ten months leading up to Election Day, 1948, and its astounding climax. The cartoons reproduced in this book first appeared on Page One of the Star. Not all the campaign cartoons used in the Star are here, of course … But the story is all here, together with the humor, wit, and sting. So is a lot of the truth.

Did you notice? The Star had THREE EDITORIAL CARTOONISTS. Three! In 1948. And many newspapers of the day had more than one.

And did you catch that other glimpse of yesteryear—“appeared on Page One of the Star”? The Star wasn’t alone. That’s how highly newspaper editors once thought of their editorial cartoons. They ran them on the front page.

But no more.

Sadly, no more.

Defeated, gutted, undervalued. Its absence, hazardous to democracy.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022