We Killed: The Rise of Women in American Comedy…A Very Oral History — a book review by Roz Warren

It has taken the American entertainment industry far too long to realize what women have always known. We’re funny. And we’ve always been funny. We’ve come a long way from the 1950s, when the only well-known female comics were Joan Rivers and the late, great Phyllis Diller, to the current comedy scene that is, happily, dominated by women: Mindy Kaling, Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, Wanda Sykes. Not to mention Rivers herself, still going strong at age 79.

We’re here. We’re hilarious. And finally, America gets it.

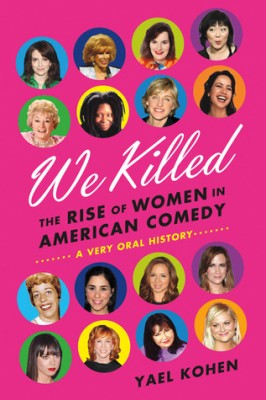

Journalist Yael Kohen takes a look at the changing role of the funny woman in “We Killed: The Rise of Women in American Comedy…A Very Oral History” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), which examines women comics and comedy writers, their context and their craft, over the past sixty years. There have been some excellent books about women’s comedy, such as the humor scholar Gina Barreca’s They Used to Call me Snow White, But I Drifted: Women’s Strategic Use of Humor (1991), and a number of recent bestselling memoirs penned by the comics themselves, such as Tina Fey’s Bossypants (2011) and Mindy Kaling’s Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? (2011). But We Killed is the first real history of women in contemporary American comedy.

Journalist Yael Kohen takes a look at the changing role of the funny woman in “We Killed: The Rise of Women in American Comedy…A Very Oral History” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), which examines women comics and comedy writers, their context and their craft, over the past sixty years. There have been some excellent books about women’s comedy, such as the humor scholar Gina Barreca’s They Used to Call me Snow White, But I Drifted: Women’s Strategic Use of Humor (1991), and a number of recent bestselling memoirs penned by the comics themselves, such as Tina Fey’s Bossypants (2011) and Mindy Kaling’s Is Everyone Hanging Out Without Me? (2011). But We Killed is the first real history of women in contemporary American comedy.

If you care about women who “kill,” it will blow you away.

Kohen interviewed 200 insiders. Comics, club owners, writers, agents, and powerhouses like Marcy Carsey, who produced both the Cosby Show and Roseanne. She queried them about every aspect of the business, then pulled the transcripts apart and reassembled them into a gabfest that’s both illuminating and entertaining. Want to know Robin Williams’s take on what a groundbreaker Whoopi Goldberg was? Curious about what Margaret Cho owes to Janeane Garofolo? Or what Roseanne owes to lesbian coffeehouses and the Unitarian Universalist church? You’ll find it here.

It’s like listening in on a far-ranging and spirited conversation among articulate and opinionated insiders on a topic—comedy—about which they care deeply. They talk about each other. They talk about themselves. They talk about the times. They tell war stories. They dish. They kvell. They schmooze. A tough, vibrant, and exciting world emerges.

We Killed isn’t a funny book. There are few quips, jokes, or one-liners. It’s a serious book about funny.

Nor is it a scholarly work. There’s no index. (An index would have been helpful.) The need to entertain precedes the need to inform. Kohen isn’t an academic. But she’s a gifted reporter, with amazing access. She talked to everyone from Phyllis Diller to Chelsea Handler, about everyone from Merrill Markoe to Mo’Nique. If you have a favorite mainstream comic, she’s probably here—as well as plenty of funny women not yet on your radar. I’m a comedy nerd myself, and I learned a lot.

Starting with Rivers and Diller and their world, Kohen takes us forward to the present day, including riffs on, among other things, Lily Tomlin and Laugh In, the Mary Tyler Moore Show, That Girl, Maude, the Carol Burnett Show, Second City, Roseanne and Ellen, Janeane Garofalo and the alternative comedy scene, Amy Poehler and the Upright Citizens Brigade, Kristen Wiig and Bridesmaids, and the game-changing significance of Chelsea Lately.

Kohen lets the players speak for themselves, weaving their observations together with concise, illuminating commentary, so the book remains a fascinating journey rather than devolving into a free for all. While her subjects clearly feel a lot of respect for each other, they hold plenty of conflicting views. But Kohen’s editing remains even handed. When Roseanne gripes about how her sitcom’s producers kept trying to undermine her, she’s followed by the show’s producers and writers, who discuss how challenging she was to work with. Between the many different angles on each topic and Kohen’s cogent analysis, we learn not only what took place and when but we also gain some understanding of why things went down the way they did.

Every woman of significance in the US comedy mainstream over the past six decades is covered—and usually heard from. (Comic performers not part of this mainstream, such as Kate Clinton, are, alas, left out.) We learn what part each played in the overall development of the genre, how she became famous, the challenges she faced, and how her peers felt about her. There’s lots of gossip, as well as some back stabbing. We also learn about the development of comedy performance, from traditional stand-up (one person, at a mike, on stage, with a spot, telling jokes) to looser and more fluid forms such as improv, conversational and observational comedy, and storytelling.

The comedy world has changed, from a limited number of venues tightly controlled by (usually male) gatekeepers, to today’s Internet-driven, wide-open playing field. It becomes clear that the fewer bookers, agents, comedy-club owners, and other gatekeepers between a funny woman and her audience, the easier it is for her to reach that audience and thrive. This book’s readers, inspired to hit YouTube to check out comics new to them, will no doubt become part of this process.

Several of the women here are true pioneers, who broke through boundaries and transformed comedy, sometimes at quite a personal cost. Joan Rivers beat the odds to become famous but was famously cast aside by Johnny Carson when she accepted a job that brought her into competition with him. And when Ellen DeGeneres, after much soul-searching, finally came out, she says, “[M]y nightmare, that if they found out I was gay I’d lose my career, came true.”

Of course, Rivers has worked steadily to this day and DeGeneres quickly reinvented herself as a talk-show host. The bottom line? These women have both the chops and the drive to get where they want to go, despite setbacks.

They also look out for each other. Saturday Night Live is a case in point. When the show first aired in 1975, it quickly earned the reputation of being a “boy’s club” inhospitable to women writers and performers (although its producer, Lorne Michaels, is universally praised for his early and strong support for funny women). John Belushi demanded that the women writers be fired and refused to act in sketches they wrote. The men in the writers’ room failed to feature female cast members, usually relegating them to supporting roles.“There was a pervasive attitude of sexism,” notes the SNL writer Ann Beatts.

She and fellow-writer Rosie Shuster responded by making sure Gilda Radnor, Laraine Newman, and Jane Curtin received air time. Beatts notes that she and Shuster, feeling “a strong obligation to make sure that the women were well served… and were not left playing.. subsidiary roles,” and they wrote strong, feminist material for them. This set the tone, and things improved, although slowly. In recent years, the “comedy powerhouses” Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, Maya Rudolph, Rachel Dratch, and Kristen Wiig established, says Kohen, “the visibility and dominance of women on the show”—to the point where she describes the current SNL as a “girl’s club.”

The struggle of female writers to make it into TV’s writers’ rooms mirrors the struggle of female performers to get stage time. At first, women writers were shut out. Treve Silverman was turned down by Carson because he believed “(t)he men would not feel comfortable.” Gail Parent was turned down for the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour because, she was told, “it’ll ruin the guys being able to curse.” But when women comic performers became popular and powerful enough to get their own sitcoms, they began hiring women writers.

We Killed is a success story. A pop culture in which women weren’t encouraged to be funny has been transformed into one that embraces and empowers funny women. But, cautions Kohen, we aren’t yet living in a feminist comedy utopia: “Funny women continue to face challenges…. Out of 145 writers working across ten late-night shows, sixteen writers are women (five of them for Chelsea Lately); out of 24 writers on Saturday Night Live, six are women, and out of fourteen performers, four are female.”

And speaking of feminist comedy utopias, the one problem I have with We Killed (besides that missing index) is that by choosing to limit its scope to mainstream performers, it leaves out women comics who have found success outside the mainstream. Kate Clinton is every bit as clever as Ellen DeGeneres, and could have achieved similar mainstream success, had she too been willing to shun political humor, hawk Cover Girl cosmetics, and remain closeted until after America fell in love with her. But, then she wouldn’t be Kate Clinton. Instead, she built a kick-ass comedy career entirely on her own terms—as have women such as Marsha Warfield, Marga Gomez, and Suzanne Westenhoefer. Adding their voices to this book would have produced a deeper and richer conversation.

About twenty years ago, I published Revolutionary Laughter: The World of Women Comics (1995), a collection of profiles of and interviews with fifty women comedians, both in and out of the mainstream. Chasing down and interviewing these gifted performers, screening and transcribing hours of tape, and editing it all into a coherent whole resulted in a book I felt did justice to the topic. And, it was such a crazy amount of work that I vowed never do to do it again! While the book did extremely well for one published by a small feminist press, I was told by many folks that it would have done even better had I focused solely on mainstream comics and “left out all the lesbians.” I didn’t care. What mattered to me was that I’d written exactly the book I’d wanted to write.

So, having been there, I don’t fault Kohen for writing the book she wanted to write, instead of the more inclusive, less mainstream survey I might have preferred. It matters more that We Killed is exactly the book she set out to write, and it’s a dazzler.

(This essay first appeared in The Women’s Review of Books)

- You’re Never Fully Dressed for That Excruciating Tax Audit Without a Smile - February 1, 2019

- Welcome to Your Local Public Library — Please Take Your Dildos With You When You Leave! - January 27, 2019

- My Resolutions for You in 2019 - January 4, 2019